Horn of Africa’s New Security Landscape: Geopolitical Consequences of the Conflict-Cooperation Dynamics

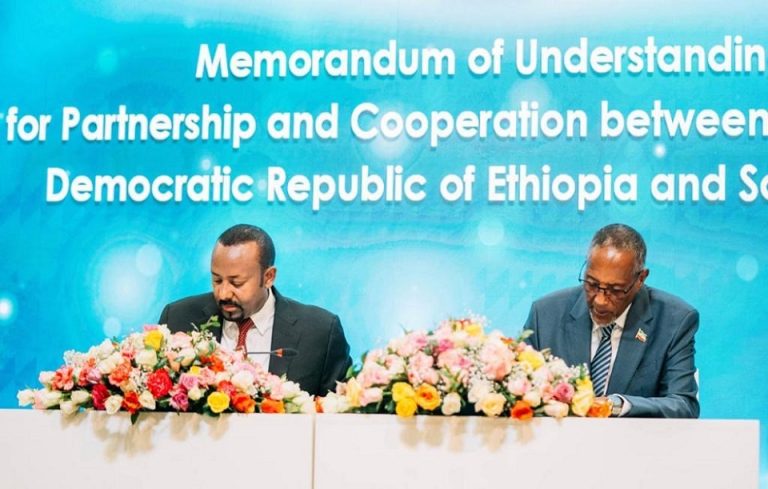

n January 2024, a crisis erupted with Somalia after Ethiopia signed an MoU with Somaliland, giving Addis Ababa access to the Berbera Port on the Red Sea.

The Horn of Africa region is at the core of regional and international contentions. It enjoys a unique location on Bab El-Mandeb Strait and the Red Sea, diverse natural resources and fertile soil, a history and the present replete with conflicts and wars within and among regional countries. The region has many overlapping and competing ethnicities and several demographic and political factors. These complexities lead to a constant shift in the dynamics of conflict and cooperation, making the region stuck in a network of regional security issues.

The Horn of Africa region has recently been going through a critical juncture that puts its stability at stake, with regional – and perhaps international – repercussions. The conflict in Sudan between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has expanded. There is political and security uncertainty in Somalia due to political divisions, the threat of terror from Al-Shabab Movement, and turmoil in the southeast of Somaliland. Moreover, Ethiopia’s efforts to access a seaport have caused tension with neighboring countries on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

In January 2024, a crisis erupted with Somalia after Ethiopia signed an MoU with Somaliland, giving Addis Ababa access to the Berbera Port on the Red Sea. Mogadishu viewed it as a violation of its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The crisis undermined Djibouti’s efforts to resume talks between Somalia and Somaliland. This coincided with foreign powers becoming active to benefit from regional shifts, boost their influence, and gain more competitive advantages.

An Expansion of the Sudanese Conflict

The cycle of polarization and tension due to the conflict in Sudan between the army and RSF – which is expanding and attracting regional and international actors – might bring the civil war in this country to a new and gloomier juncture. This is possible due to the dramatic shift in the map of influence and power balance on the ground, the relative change in local alliances, and the continued political stalemate. The following are the most significant developments in Sudan over the last few months.

Expansion of battles toward the middle and east of the country. In December 2023, RSF took control of the strategic al-Jazirah state and its capital, Wad Madani – the south gate of Khartoum near the Kassala and al-Qadarif states on the Eritrean and Ethiopian borders. The Sudanese army mobilized its allies of armed movements and tribes to regain control of al-Jazirah. The escalation of fighting toward the east is considered a turning point, the impact of which goes beyond local conflict dynamics to its regional dimensions, perspectives, and alliances.

Armed movements have relinquished their neutrality due to several factors. These factors include the expansion of battlefields and indications of a prolonged war, the tribal factor and deeply-rooted historical animosities, the pragmatic calculations of domestic actors and temptations by both sides to entice them, and the external factor. Regional actors have incentivized these movements and tribes to align with one side or the other.

Some armed movements in Darfur, notably the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) led by Jibril Ibrahim – the incumbent finance minister and the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) (Minni Arcua Minnawi wing-Darfur governor) – saw RSF’s expansion as a threat to their field gains and economic activities, which they multiplied recently by exploiting the vacuum left by the Sudanese army.

Therefore, JEM and SLA preferred an interim rapprochement with the Sudanese army and announced that they would join forces in mid-November. Most of these two movements’ troops are located in northern and western Darfur. In addition, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), led by Mustafa Tambour, has supported the Sudanese army since late July 2023.

However, the alliance between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu – which controls a large swath of territory in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states – and the Sudanese army attracted attention recently. This alliance aims to prevent RSF and their allies from entering Dalang, the second-largest city in South Kordofan state. In January, a senior SPLM-N commander denied any alliance with the Sudanese army, reiterating a contrast in his movement’s goals and military doctrine with those of the Sudanese army. He pointed out that SPLM-N’s firm and declared position is to “dismantle military institutions and restructure them on new bases.”

There is a growing risk of internationalizing the Sudanese conflict. This was evident, for instance, in Khartoum’s suspension of its membership in the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s boycott of IGAD’s summit in Uganda on January 20. After almost seven years of rupture, Sudan also resumed its ties with Iran. This enabled the Sudanese army to acquire Iranian drones, although such development might turn Sudan into a theater of regional and international competition. Khartoum also seems helpless toward Eritrea’s growing engagement and influence in Sudan. There are reports about Asmara’s involvement in the militarization of tribes by establishing six training camps for five armed groups from eastern Sudan and a sixth from Darfur. The step reflects Asmara’s security concerns and ambitions to regain its historical regional influence and gain the advantage of bargaining at the regional and international levels. This development raised fears about renewed tribal conflicts in the region and the likelihood that civil war might spread to eastern Sudan.

The decline of settlement chances in light of both parties’ stubbornness to the conflict, their increasing stakes in their maneuverability, and their making decisive shifts in the field impact domestic dynamics and international positions in their favor. Moreover, the multiple forums and initiatives for solutions and lack of internal and external consensus on them – among other complications – undermine diplomatic efforts to establish a suitable environment for political settlement in Sudan and push toward an escalation of war that reached disturbing levels. The Transitional Sovereignty Council also rejected the Security Council resolution issued on March 8, calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities in Sudan during Ramadan. It urged all warring parties to seek a sustainable resolution through dialogue and removing any obstruction to the humanitarian aid delivery.

No objective indications yet call for optimism over the two sides’ convictions regarding the feasibility of peaceful options to end the conflict. Efforts led by the Sudanese Coordination of Civil Democratic Forces (Taqaddum) led by former prime minister Abdullah Hamdok have gained increasing momentum to build a national consensus to impact political interactions in the country, press to end the war, and put the democratic path back on track in parallel with the return of international and regional attention on the Sudanese issue. This issue has retreated due to preoccupation with the Gaza War and the geopolitical and security tension in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

-

The Man Who Saved a Forest: Tommy Garnett’s 25-Year Fight for Tiwai

Edited By : Widad WAHBI Tiwai Island in Sierra Leone has officially been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, thanks to... Uncategorized -

At the Women’s Africa Cup of Nations, Algeria Plays a Different Game

Edited By: Africa Eye Football has long been more than a game. It is a global stage — a place where... Uncategorized -

Somalia: Al-Shabaab Launches Large-Scale Attack on Key Military Post

Edited by : Widad WAHBI Al-Shabaab militants launched a large-scale assault at dawn on Wednesday targeting a military base and the town... Uncategorized -

Afrique du Sud : Ambitions nucléaires et tensions internationales

Rédaction : Fatima BabadinDans un contexte de volonté affirmée d'indépendance diplomatique, l'Afrique du Sud a exprimé son ouverture à des... Uncategorized -

Algeria Scandal in the African Union: suspicious briefcases filled with cash have been circulating in the hotel corridors hosting heads of african delegations.

Africa Eye Editorial Board .A bomb exploded within the African Union after journalistic sources revealed Algeria's return to “briefcase diplomacy”.... Uncategorized -

Senegal: Lifting Parliamentary Immunity Opens New Chapter in Anti-Corruption Fight

The Senegalese political landscape was recently shaken by the lifting of parliamentary immunity for Mouhamadou Ngom, an opposition MP with... Uncategorized

Follow the latest news on WhatsApp

Follow the latest news on WhatsApp  Follow the latest news on Telegram

Follow the latest news on Telegram  Follow the latest news on Google News

Follow the latest news on Google News  Follow the latest news on Nabd

Follow the latest news on Nabd